I was at a photography industry event recently and brought along my newest camera (the Panasonic GX7 which I still need to write about). It was an informal, social gathering and I was helping the social media efforts of the group, so I pulled it out to snap a couple pics. One of the other photographers asked about the camera. Question 1: “What camera is that?” Question 2: “How many megapixels does it have?”

Since the first digital cameras were released for mass sale, camera-makers have lined up to tout their ‘bigger this,’ and ‘faster that,’ and ‘more of these’ – but through all the clutter, the one number that most camera buyers gravitate toward are the megapixels. But what do you really need?

First, let’s look at what ‘megapixels’ are, and how they’re calculated.

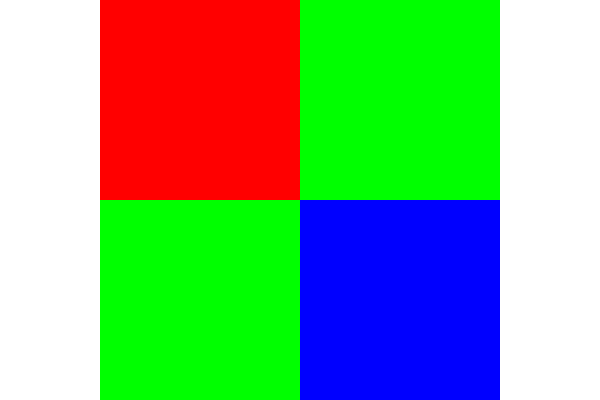

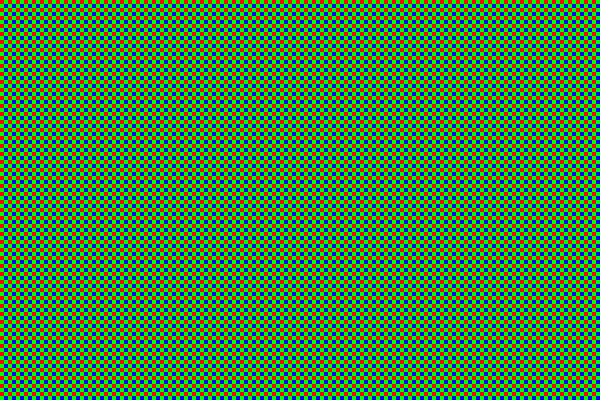

On a digital camera’s sensor, there are a bunch of little tiny squares called ‘photosites.’ Think of a photosite as a single square, that only sees 1 color; red, green or blue. The more red is in a picture, the more light will be picked up in the red squares, or pixels. These photosites are placed onto a sensor, typically, in what’s called a “Bayer Array” (or ‘Bayer Filter,’ which you can read more about here).

If the above were a camera sensor, it’d be a 4 Pixel camera. It doesn’t matter how big or small a pixel is; a pixel is a pixel. These 4 photosites each gather light, then a fancy algorithm interpolates the data (fancy speak for ‘figures out’) what the sensor is ‘seeing,’ then puts the information together to show you a picture. A 10×10 square of these photosites would be a 100 pixel sensor, and a 100×100 Bayer Filter would be a 10,000 pixel sensor.

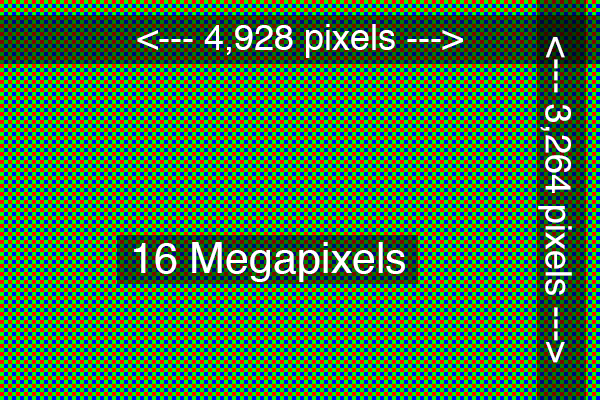

Now we’re starting to get a sense for how many photosites are on a camera’s sensor. A Nikon D5100 has a sensor that measures just 23.6×15.6mm, and contains a Bayer Filter with a 4,928×3,264 grid of photosites, which works out to about 16 million photosites, or a 16 megapixel sensor. The Canon 60D sensor measures 22.3×14.9mm, and has 5,184×3,456 photosites, or just under 18 megapixels. Yes, that’s 16 and 18 million little red, blue and green dots in a sensor that’s smaller than a USPS Forever postage stamp. Does that mean the Canon is ‘better?’ Not really.

Let’s look at the sensor size and assume for a moment that the number of photosites on both sensors are identical. If they both had 16 megapixels, but the Canon sensor is smaller, each photosite on the 60D would be smaller and therefor be able to receive fewer photons of light, where the Nikon sensor would be more sensitive per photosite because each is larger. Do you take a lot of pictures at night, or in dark places? Larger photosites are a good thing because each can receive more light.

The bigger story, tho, is in how photos are used today. How many photos have you taken in the last hour? In the last day? In the last year? Of those, how many have you shared by showing someone the back of your camera? By emailing? By posting to Facebook, or another online gallery? Over 200,000 photos are uploaded to Facebook every minute! A glance at your newsfeed will show photo after photo being uploaded from phones and cameras alike, not to mention graphics that are not photos per se, but are still pixel-based images. The largest photos that Facebook displays are cover photos which take up the entire width of a person’s or company’s profile page; or 851 pixels. If you want to size your cover photo to be ‘perfect’, you’d size your photo to 851×315, or ~268,000 pixels. Yes, that’s a .27 megapixel image! See more on Facebook and other social media image sizing here.

Oh, but you’re going to print your photo? 4×6”? 5×7”? Let’s go big and say you’re going to print an 8×10” photo. Printing is measured not just in how many pixels are used, but how many pixels – or points – per inch that are printed. For most home printing you’d be fine at printing at 175 points per inch, or ppi. Newspapers print in the 140-170 ppi neighborhood, where high quality magazines are often in the 240-300 ppi range. Let’s say, then, that you want to print that 8-10 at the maximum quality – or 300 ppi. 10 inches, at 300 pixels per inch… that’s 3,000 pixels on the long side – and 8 inches at 300 ppi, that’s 2,400 pixels on the short side – 3,000×2,4000 is only 7.2 million pixels! Give yourself some fudge room to crop, say a half inch on every side, and you’d still only need a 9 megapixel camera.

Now, there is something to be said for clarity. If you pack more pixels into that sensor, you can get better definition in crisp, hard lines. If you’re really careless and crop down your photos (throwing away pixels), you need the extras – but that’s just poor form; a crutch to let you be sloppy. The Nokia Lumia 1020, a phone that launched in 2013, has a 41 megapixel camera on board, which produces photos that look great in brightly lit spaces, but the sensor is just 8.80×6.60mm – smaller than buttons on a dress shirt. Tiny sensor + lots of photosites = Poor low-light performance.

Camera buyers today have been conditioned to equate a megapixel count with quality, but just like the technology that continues to advance in computers, and microwave ovens, the image quality of a camera is not based solely on the sensor and how many photosites it has. The processors that interpolate the images, the anti-vibration mechanisms, and even the sensor low-light capabilities have all improved drastically over the last few years with no end to the up tics in sight. Even more, the software in today’s digital cameras and their ability to guess what you care about in the photo and make (extraordinarily) fast adjustments to help you, has developed leaps and bounds recently, and that has nothing to do with the sensor itself.

When do megapixels matter? If you’re going to print big – really big – billboard-size big – they might. If you photograph very detailed things, more pixels can be helpful. If you need to be able to zoom in to your photo to analyze something, eg a laboratory of some sort, more pixels might be nice. The size of the sensor will also effect things like dynamic range (how many stops of light your camera can perceive) and depth of field, so as the sensor size goes up it’s natural for the number of pixels to increase. As I alluded to earlier tho, I prefer larger photosites to a certain number.

So, how many megapixels do you really need? Not as many as you think. Pay more attention to the fundamentals and it won’t matter how many megapixels the latest gizmo has. Forget the megapixels, and keep making great photos!